I’m a monitoring nut. I’m a firm believer that you can’t improve what you’re not measuring, so it’s always fun for me to try to quantify everything at work that people care about – even the stuff that’s generally too challenging to “pin down” to bother. So when the question at work comes up of “how do we make our developers more efficient”, the only response I can come up with is “well, how are we measuring it?”

The conversation around developer efficiency at larger software shops is of course worth having. But in order to make quantifiable progress in this area, we’ll need to have some numerical sense of the friction that developers face in their day-to-day tasks. Here, I’ll briefly describe one method I’ve been using for the last few years, which has served me well enough to start making useful comparisons across months, teams, and companies.

Comparing to a Baseline

No measurement can be useful without units, right? A number line, an axis, some concept of “zero”. It doesn’t matter where on the number line this zero is; its main purpose is to be a easily-recognizable fixed point which we can compare to other points (and indeed, it allows us to compare points to each other).

In my scale of developer friction, the “zero point” for a software development (or ops) task is “how long this would take me to do for my own project on a Saturday morning”. No company infrastructure, no automated test suite and deployment process, no metrics or log aggregation or responsive alerting. Just you, one server with root access, and one or two apps running on that server. In this tiny-world model of your unit of work, how much time do you have to spend in order to see it through?

This kind of comparison against the requirements of a company’s SDLC might not be perfectly “fair” for a number of reasons, but by comparing against this baseline, we can at least begin to quantify the help/hurt of that company’s infrastructure.

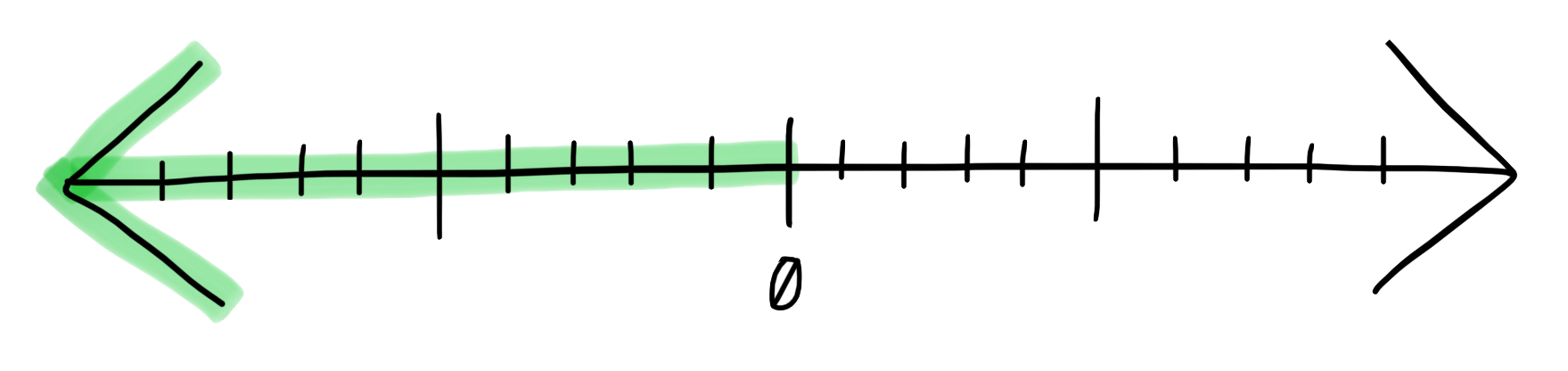

Reducing Friction

A developer facing less friction in getting their change safely validated and deployed is always a good thing, and work in this direction is usually very deliberate. Larger software companies will have entire teams dedicated to the effort. After all, if you can save each developer 5 minutes of time in deploying a change for example, you’re looking at dozens of hours (and thousands of dollars) saved per month.

Examples of reducing developer friction below the “baseline” include:

- A CI/CD system which will automatically run

terraform applywhen a PR to a repository containing infrastructure as code is merged - An internal profiling system that allows developers to spend less time figuring out what caused an app’s memory usage to spike, and more time fixing it

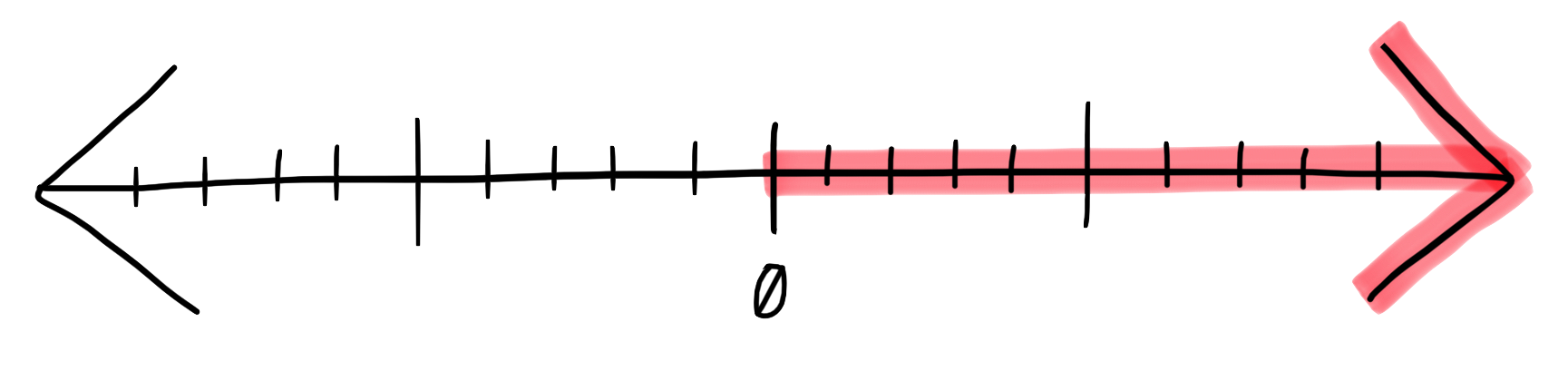

Increasing Friction

In contrast, “increased developer friction” almost universally happens by accident, or at least accumulates slowly over the lifetime of a software product.

Despite first instinct, it doesn’t generally come from leadership having bad prioritization, or coworkers who “just didn’t think things through enough”. Instead, it’s more due to the top-down necessity of additional security/compliance measures, or more often in my experience, added process as a direct result (a “follow-up”) of a previous outage in an effort to avoid the same thing happening again.

Examples of increasing developer friction above the “baseline” include:

- A suite of unit tests that include a few “flaky tests”, which occasionally fail after 10 minutes and need to be re-run before a deployment can be triggered

- A change that needs to be executed across several different applications in different places, in a specific order or all at the same time

A Real Life Example

One job I’ve done in the past made a particularly good example of this model. It involved the deployment of updates to configuration files that “lived” in various places – some rendered into our base machine image, some rendered at instance creation time, and some pulled dynamically at runtime (using something like Consul).

In order to update a configuration file rendered into the base image, we needed to spin up a bare VM, install dependencies, run all provisioning scripts, save the image, hardcode the new image ID in various other places, and create some “real” VMs to verify it worked. This is significantly more friction than our “Saturday morning” baseline – the entire process took hours, and would often fail in the middle since it wasn’t performed very often.

In contrast, updating an instance-creation-time configuration was easy, and just required making a pull request and then running something like Ansible or Chef on each already-existing VM. This is about even with the baseline – I had to update the file, make a PR, and run a script or two in order to make sure the instances were up to date.

And in comparison, updating a dynamic configuration took barely any thought at all. Our deployment system was always synced to the Git repository, so as soon as the field was updated there, each instance would start seeing the new value immediately. This is much less friction than the task would have been by myself – the update only required a short pull request, and the deployment happened automatically.

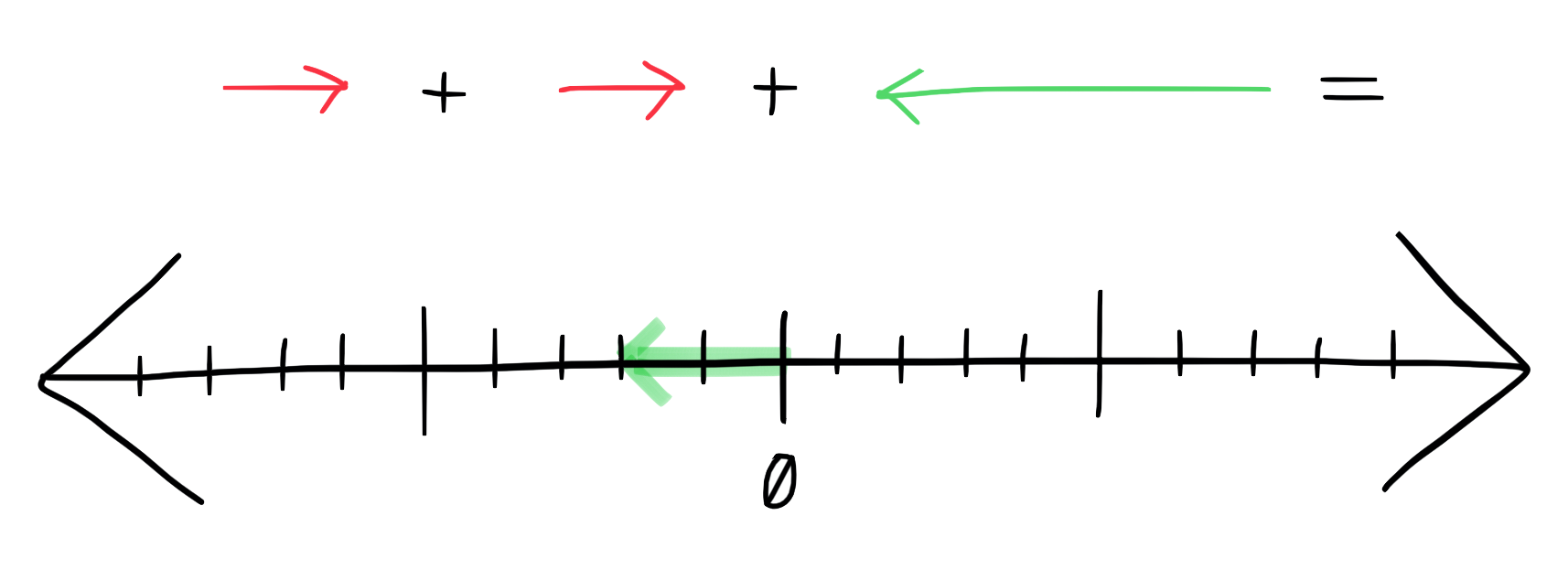

Vector Addition

Of course, any real software project will be more nuanced than any example in a blog post. The real friction your developers feel is affected by dozens of small factors, some negative and some positive, each costing or freeing a few minutes of their time.

Fortunately, there’s no complicated math here, and the total friction they’ll experience is just the sum of each individual gain or loss of efficiency. So if a developer loses 10 minutes of her time setting up explicit new permissions for her app, and loses 10 more waiting on a suite of unit tests that have nothing to do with her change, but gained 30 minutes back by having the CD system roll out her change to each region (rolling back automatically when needed, so she doesn’t need to watch dashboards) – that’s a 10-minute win overall!

At the end of the day, requirements will often dictate that making change is slower than it would be on your own server on a Saturday. But hopefully, this can be a useful, concrete way to start telling the difference between a developer feeling frustrated or empowered by the company’s infrastructure, and to see if you’re really making progress.